Mr. H. P. BELLOC

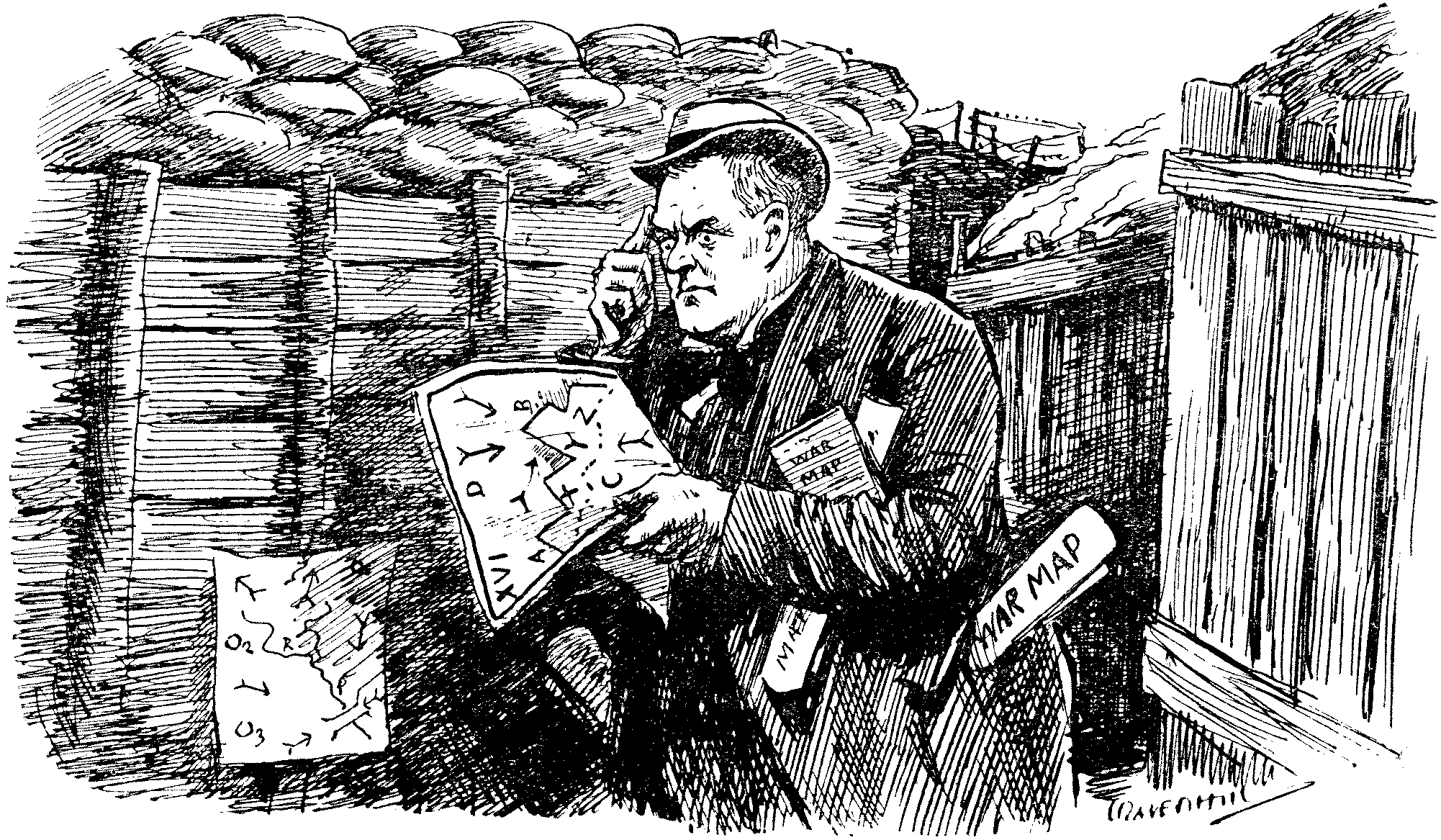

I rise to bring forward only one point that may seem to be a, detail to Members of this House, but which I consider to be one of some importance, and which can only be brought forward, at any rate adequately, on this one day of the year and on this one Vote. It has been touched on in the speech which Ave have just heard, and just touched on only for one moment, in the speech made by the Hon. Member behind me (Mr. Bellairs). I refer to the fortifications of the land fronts of the naval bases of this country. It seems only a small point, a technical point, and one which experts would discuss better than a Member of a popular assembly. I want to try to show the House, or, at any rate, to convince the House from my own point of view, that the matter is of exceptional importance. In the first place, I ask the House to consider what any great Power does when it is 1414 fighting, and what the strategical problem is. You read in your books that he attempts to strike at the heart. That, as a metaphor, means nothing more than that the defences of this country lie in the Fleet. What an enemy attempts to do when he is striking, as the metaphor goes, at the heart of an opponent is to get at the vital organism of the defence and destroy it. Politicians have talked—I do not think any soldier has talked—of a raid on London. The idea is absurd. An enemy would have for his prime object, especially in the first stages of the war, the crippling, in some way or another, of the British Fleet; and unless the British Fleet were in some way or another crippled, although outlying portions of the Empire might be menaced and might be lost, there would be no compulsion on this country to give way. If the Fleet were crippled, that compulsion would be felt within 24 hours. It would be felt by the simplest of all processes—the immediate rise in the price of food to famine prices. It is as an integral part of the Navy, as the most vital of all vital organisms of the Navy, that the base and a certain measure of land defences are of importance. In the first place I may say, for what my personal opinion is worth—but it is the opinion of the vast majority of those who have studied the subject—that an invasion is, I will not say impossible, because nothing is impossible in war, but so improbable that all those who are concerned in the defence of this land do well in putting it last among the possibilities of what an enemy might do to us. An invasion in force, an invasion such as have been in the past the invasions of Germany, France, Russia, or Italy means not only the transport of a great number of men and a vast amount of material, but also absolutely secure communication, and it means that to so obvious a degree, and it is so startlingly true even on land, that the greatest conquerors, if their communications during an invasion in force had been endangered, if only for a few days, would have had the whole success of their adventure imperilled.

§Mr. H. BELLOC

I should say that the invasion of Egypt hardly corresponds to the invasion of one Great Power by another. It was the invasion of an Eastern people, and I do not think that it can be done as between one great European Power and another. Another reason which makes me think that an invasion 1415 in force could not take place is that long before this invasion in force could be accomplished peace would have been made. Long before it would have been possible so to cripple the Navy as to maintain communication between the country being invaded and a large invading Power the pressure would have been put on the governing classes by the poor to compel peace. The price of food alone would do that. Though it is infinitely more likely, I do not believe, even in a raid by a large body of men, by a division of 10,000 men, but I do believe in the possibility, or the probability in our present condition, of a raid by a much smaller body of men, who may strike at the vital organism of the naval defence of our country. I ask the House to consider for a moment, technical as the matter is, and to some extent unfit for popular discussion, what a modern naval base is and why our naval bases at the present moment are in a sense so much more important, especially so much more important in the first days of the war, than they were, say, during the Napoleonic era. With every step in advance in science, with the one exception of wireless telegraphy, bases are becoming more and more immediately and continuously essential to modern fleets. In the first place, consider the rapid exhaustion of material under modern conditions of fighting. On land the problem with which all experts in tactics are most concerned just now is how to feed what we may call metaphorically the fighting line, the power in front, with sufficient material, so rapid is the exhaustion. The Navy must depend on the great depots at the naval bases. Secondly, there is the question of repairs. A modern fleet cannot keep the seas without being in touch with the naval bases for repairs, and a modern fleet, more than was the case in the past, depends for its efficiency on the co-operation of all its units. Any proportion of its units sent off for repairs must return as soon as possible to the battle line. Complete victory at sea is rare, and even in the case which occurred at the close of the Russo-Japanese War extensive repairs were necessary. It is essential to a modern fleet that repairs should be readily obtained, and they can only be got at our naval bases. A further point is the continued necessity of these things. A modern fleet must be in touch with its base to be an efficient fighting machine. In regard to fighting in the near future, 1416 it is upon our Home bases that all discussion would turn. One further argument in favour of Home defences. In the case of an attack the enemy would consider the point on which it would concentrate it, and would be certain to fall on one of the small number of points chosen. We may be absolutely certain that if there was a German invasion of French territory that there would have to be a siege of one of the four great fortresses; or, in the case of an invasion by the French of Italy, it would be absolutely necessary that the French should attempt to secure the highest passage of the Alps. The smaller the number of the points of objective the more certain is there to be concentration on one of them. In our case the four vital points of attack are Portsmouth, Plymouth, Rosyth, and Chatham, and we have to consider what an enemy would do. If war were declared between this country and a great Continental Power, it is unlikely, and, I would say, almost impossible, in the present balance of naval power, that there would be an attack by battleships against battleships. The very first thing a foreign Power would consider would be how to get at some vital point, and undoubtedly they would decide, even with the great risk involved, to attack Portsmouth and the dockyards, probably by night, taking advantage of fog, or bad weather, in an endeavour to pierce one of these points. The hon. Gentleman opposite (Mr. Ashley) said our naval bases were practically open. They are not only "practically" open towns, they are actually open, and even with the smallest force, damage could be done. Land communication and railways could be destroyed, bridges blown up, and so forth. It would be easy to damage the vital parts of a naval base. One graving dock could be ruined in a few moments by the use of dynamite. That applies to all the complicated machinery of modern warfare.But I do not mean to suggest that enormous expense should be incurred on strongholds. I see no reason for constructing in England such places as are seen at Spezzia, Toulon, or Cherbourg. We need fortifications on a smaller scale. No one fortifies to make a place impregnable. Napoleon's great maxim was "fortify to gain time." Every fortification is a draft on time, and is the introduction of the element of time in your favour. There can be no doubt, especially at the opening of a naval campaign, that we shall require that sense of security over very short periods of time, 1417 though I think it is extremely unwise to attempt to fortify English naval bases on the scale on which the great Continental bases are defended. Take the case of Rosyth. At the present moment it is proposed to defend that place with three batteries on the level of the water, which should be sufficient to prevent attack by destroyers or torpedo boats. But dominating these batteries is Mons Hill, which would be a suitable place for a landing. A small raiding party provided with artillery could capture Mons Hill, destroy the Forth Bridge, and disarrange the conduct of the port behind.

Portsmouth is ideally situated for defence by land. It is a peninsula cut off by Portsdown. With the present range of artillery, Portsdown could be wholly swept from one fort; nobody could live on it. We do not need have very large and expensive fortifications, we need one permanent work at Portsdown. With one, or at most, two, you could cover your base at Portsmouth, which is, I should imagine, a permanent work in the centre, or certainly two permanent works at either end of the ridge, would be sufficient. The arguments against this are the arguments of the Blue Water school, that if your Navy is sufficiently strong nothing else is needed. If anyone says that an overwhelming fleet would prevent an invasion in force, I will listen to him and I will agree. And if anyone says that a large raid is impossible, I will listen to him, and perhaps agree. But if anyone says that our supremacy would prevent a short raid at a vital point, then I do not think that anyone who has considered the matter could agree. Another argument is the argument of the Treasury: "Are we to be led into this expense? If we are to spend money let us spend it mainly on the Navy." That is a perfectly sound argument against fortification on a large scale. Fortification on a large scale of our naval bases at present would be folly. If we were to attempt a permanent and expensive fortification of our great commercial ports it would be wrong. We should have small single works—not a ring of fortifications—by which the means of approach to a base would be checked for three or four days. That would be worth our while, and is, I think, an absolute necessity. If technical details had received more attention in this House, this matter would long ago have been settled. To any man who knows the temper of this country, the type of Press which influences public opinion, and the 1418 way in which that public opinion veers round in moments of panic or excitement, one thing is certain, that if we are engaged in a European war we shall begin to fortify the land bases; and do it in a hurry, do it badly and far too expensively. I only plead that we should do it on a smaller scale and in time of peace.